Young, Gifted, Black, and an Eye Transparent

I am still in the “Tan Journal.” And I am still going to the Van Pelt library at UPENN almost daily. I am trying to put it all together: I am trying to link the traditional Islamic knowledge I was learning with my studies in college, my independent research into ancient civilizations and various religions and metaphysical practices, with the social and political history of Islam, with my experience as a Sunni Muslim convert in America.

In the process, I was pulling a lot of books down from the shelves of Van Pelt. I had a lot of questions, and I needed clarity. Unlike during my days at Amherst, however, I did have a framework in which to operate. Traditional Islamic knowledge was the means by which I was to evaluate what I was reading.

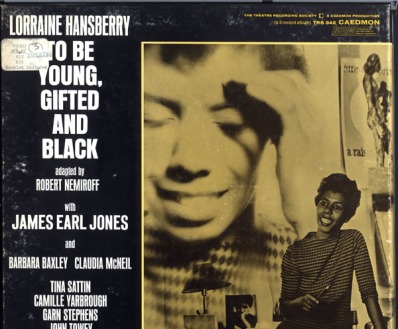

One day while at the library, I came across Lorraine Hansberry’s “autobiography,” To Be Young Gifted and Black.

Even as I write the title and look at the book on Amazon, my heart strings are pulled. The title resonated with me profoundly, for it expressed what I saw in the black community at Amherst and what I was hoping for for black folk with the final arrival of traditional Islamic knowledge (coming from a black African man!). At Amherst, during my nationalist days, I saw the tremendous potential in young black folks who, to varying degrees, were becoming politically, socially, and racially conscious. As we unfolded into the knowledge of self, and we embraced self and embraced kind, we could finally fulfill our potential here in America. We could: “Be all we can be and more….”

The image of Lorraine Hansberry and the book title not only reminded me of the latent potential in “the souls of black folk,” it reminded me of a different time: a time before the killing of Malcolm, of King or of Robert Kennedy–before the systematic assassination and destruction of black activists and their organizations by J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO. Reading passages and looking at the photos in To Be Young Gifted and Black reminded me of a more hopeful time in black America—a more “innocent” time.

With that sense of innocence came the sense of duty to raise a generation of children—to have self-loving, gifted, and black children guided by the light of Islam—and help them realize their, what would have been previously unfathomable, potential. That is, we would raise children who would grow up being encouraged to let their talents bloom; they would be so filled with wholesome self-love and accomplishment that they could not be traumatized by any sense of inferiority or racism. We would through them—through these young, gifted, and black children—heal ourselves from the centuries of trauma that permeated our own psyches. They would be the living expression of a triumph against multiple generations of struggle against racism, self-hate, self-ignorance, and worst of all, ignorance of God. That had been my hope, and when I saw Lorraine Hansberry’s book, those sentiments enveloped to my heart.

Although at this stage I was no longer what I would call a “black nationalist” (although some folks might think otherwise), one could not ignore that the overwhelming majority of converts in Philly were African-Americans, and that these converts brought with them into the Deen the challenges that black folk, in general, were confronted with. Also, there could be no denying the tremendous talent that is in African-Americans, but this talent needed to be harnessed, and it needed to be given a positive and life-affirming expression. Genuine Islam—I was certain—would provide African-Americans with that.

We could stay in touch with our past. Our past should not be dismissed or discarded with what has almost become a platitude from the immigrant brethren in Faith about how “we are all Muslims,” and we don’t need to be obsessed with color and race. As I would write in the Journal: “By knowing the past, in-shaa’ Allah [God-willing], African-Americans can gain understanding of who they are, where they’ve been, and by the Grace of God what they can be.” We could learn our history to empower ourselves; however, unlike before, we could evaluate our past from an Islamic perspective to attain proper understanding, proper direction, and proper guidance.

I was also doing a lot of Journal reading during this period. I was spending a lot time in my memories of Amherst. And as I skimmed, To be Young, Gifted, and Black, and I reflected upon that era, I reflected upon an occasion when, perhaps arguably, the hippest Brooklynite in the Valley (I’ll call her “Spice”) picked me up at the bus stop and we drove down Route 116 in the Saab (maybe the top was even dropped), while Sly, and the Family Stone’s “Everyday People” blared on the radio. It was a beautiful day; I could feel the sun on my skin, and in my face, thinking about the warm, deep, centered vibe I picked up from “Spice” (the vibe which she usually gave off), and the warmth and optimism of the music of that time. This is what it meant to be young, gifted, and black, and I was diggin’ it… diggin’ it to the maximum. And it was this sense of warmth and wholeness that I wanted to see a generation of black children grow up upon—with Islam, of course, and without the haraam.

It was also during this period that I discovered the “Transcendentalist writers” of Massachusetts. Khalil had been telling me while I was in college that I have to read these guys. I refused—largely because I wasn’t interested in what some DWMs (DWM = Dead White Men) had to say. I wanted to learn about my people and my history. As I said, by the time I made it to Philly, I was largely over my hardcore black nationalist sentiments, and I was more read to give these DWMs a read.

The same day that I discovered To Be Young Gifted and Black, I also read some of the Essays of Emerson. This was a turning point in my early days in Philadelphia. For one, Emerson (and even more so his student, Thoreau) helped me endure the long cold winter to come in the city. More significantly, they spoke of the value of language, its relation to the natural world, and the importance of purity of expression. Among the quotes that struck me and I copied down into my Journal was:

“A man’s power to connect his thought with its proper symbol, and so utter it depends on the simplicity of his character, that is, upon his love of truth and his desire to communicate it without loss….”

Immediately, when I read this, I thought of “Jazz Man,” and his ability to speak to the heart of the matter free of all pretense. Also, I copied:

“Words are signs of natural facts. The use of natural history is to give us aid in supernatural natural history; the use of the outer creation to give us language for the beings and changes of the inward creation. Every word which is used to express a moral or intellectual fact, if traced to its root, is found to be borrowed from some material presence.”

Also from Emerson I copied:

“Have mountains, and waves, and skies, no significance but what we consciously give them, when we employ them as emblems of our thoughts? The world is emblematic. Parts of speech are metaphors, because the whole of nature is a metaphor of the human mind.”

It was those walks late into the Valley night with the “Jazz Man,” the discussions we had and his ability to speak in images—in verbal hieroglyphics—that had encouraged me to go on my “Quest”–to seek the Truth. And it was during the time after Jazz Man left the Valley that I would go on long walks in the woods with my Yusuf Ali,* pondering various verses commanding people to reflect on the natural world. All of Nature was not merely a “metaphor for the mind,” but it was all a sign of the Existence of One, Perfect, Incomparable God, and I was trying to make sense of who God was and how to submit God.

Above all, Emerson reminded me of Home. The night before, I had had a conversation with the “Artist” (and Imam) that among the things I missed most about the Valley was having a sense of vision—of having the sky overhead and the feet planted on earth. Then, I discovered Emerson the following day. Emerson gave words to the feelings I experienced in the Valley.

I would copy: “The health of the eye seems to demand a horizon. We never tire as long as we can see far enough.” And:

“The sky is the daily bread for the eyes. What sculpture in these hard clouds; what expression of immense amplitude in this dotted rippled rack, here firm and continental, there vanishing into plumes and auroral gleams. No crowding, boundless, cheerful and strong.”

In my mind’s eye, I was transported back Home, to breathing fresh air deeply into my lungs, cloud gazing, silence, and trying to drive my insight to pierce through the veils of this world so I could realize the Truth. One passage from Emerson’s “Nature” struck me harder than any other:

“Standing on the bare ground–my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite spaces–all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball….”**

And although I believe this image was drawn with the intention to mock Emerson, I could totally relate:

In those final weeks of Amherst when I spoke of wishing to devour horizons with my eyes, this is what I meant. I felt like nearly disembodied vessel of perception that nourished itself in the beauty of Nature. I was glad to see that I was not alone in what I had experienced. Emerson was helping me make sense of the experiences I had had in my beloved Valley. As I would copy into the Journal from a book that I did not record its title: “By the height of Emerson’s perceptions, he was able to bring a part of New England closer to the mind….” I could see, I could feel, I could smell Western Massachusetts. And I could soar again to those exhilarating elevations of thought and feeling that I had come to love while being in the Valley—although, I was currently dwelling in the inner city of West Philadelphia.

_____________________________________________________

* I’m not claiming that Yusuf Ali’s so-called “translation” of the Qur’an is reliable—quite the contrary–but it is what I had at the time, and I didn’t know any better… not that ignorance is an excuse Islamically.

** One should not understand that “space” is absolutely infinite, but rather that space is vast. Also, it’s important to note that Emerson’s claim in that passage that he becomes “one with God” or a “particleof God” are not Islamically valid. As profound as these experiences may feel, the person does not person “unite with God”–not his physical body, nor his mind, nor his soul. The body, mind, and soul and all their states are not God nor a “part” of God. These different states of are creations of God. God is not a temporal or spatial being.

I’m absolutely Speechless.And I thought all the good writers,lovers of langauge, and classical writers(and quotes from The classics) had long ago passed………Reading through these jems,I realized ,we that struggle to perpetuate classic art,have in our mist and community one to drink from………AL HAMDULILLAH!

Your words just reveal the truth maa shaa’a l-Laah.. Gems, true gems.. al Hamdu li l-Laah

My first view of the new Day

A word that is here to Stay

Beautiful writing of a beautiful soul

Please keep staying in your role

A writer is what a writer is

And for you one cannot dismiss

🙂 Baaraka l-Laahu beek

Thanks you all, and praise be to Allah.